Welcome to Planet Days! A roundup of the latest climate news and what it means for our Planet. If this was forwarded to you, smash that subscribe button:

It’s Friday, which means we’re giving you a three-minute climate take on a big story from the week. This morning, that story starts in Eastern Europe:

At the surface, the ongoing tension over Russia and Ukraine is a geopolitical crisis flirting with an energy crisis. But dig a little deeper, and it’s got climate crisis written all over it.

With Russia amassing over 100,000 troops at Ukraine’s borders, the European Union and its allies are in a tough position:

Should Russia invade Ukraine, the United States, eager to defend a sovereign, democratic state, wants to slap sanctions on Russia.

But for the E.U., it’s not so simple: Over a third of its natural gas is from Russia, and upsetting Russia could compromise that supply in the middle of a cold winter.

This is where it gets interesting through a climate lens.

Say Russia invades Ukraine, the Western powers move forward with sanctions, and in retaliation, Russia cuts off natural gas supplies to Europe. Should this all happen (and even if it doesn’t), the U.S. aims to send liquified natural gas to the E.U. fill any energy void left by Russia.

Unfortunately for the Planet, liquified natural gas is decidedly not clean:

Extracting it can release earthquakes, air pollution (disproportionately hurting Black and brown communities and old people), and methane emissions — a greenhouse gas 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Plus, the Planet does not care where or why we burn carbon (even if we do it in the name of DEMOCRACY!); she will heat up regardless.

Though much attention is focused on Russia-U.S.-E.U. tensions, little is focused on the climate problem here: Lacking enough clean energy, Europe is committing to burn massive amounts of imported natural gas to get through the winter.

The E.U. currently gets 60% of its power from non-emitting sources, like renewables and nuclear. But these sources alone can’t keep up with demand, forcing countries to turn to Russia for cheap, dirty fuels.

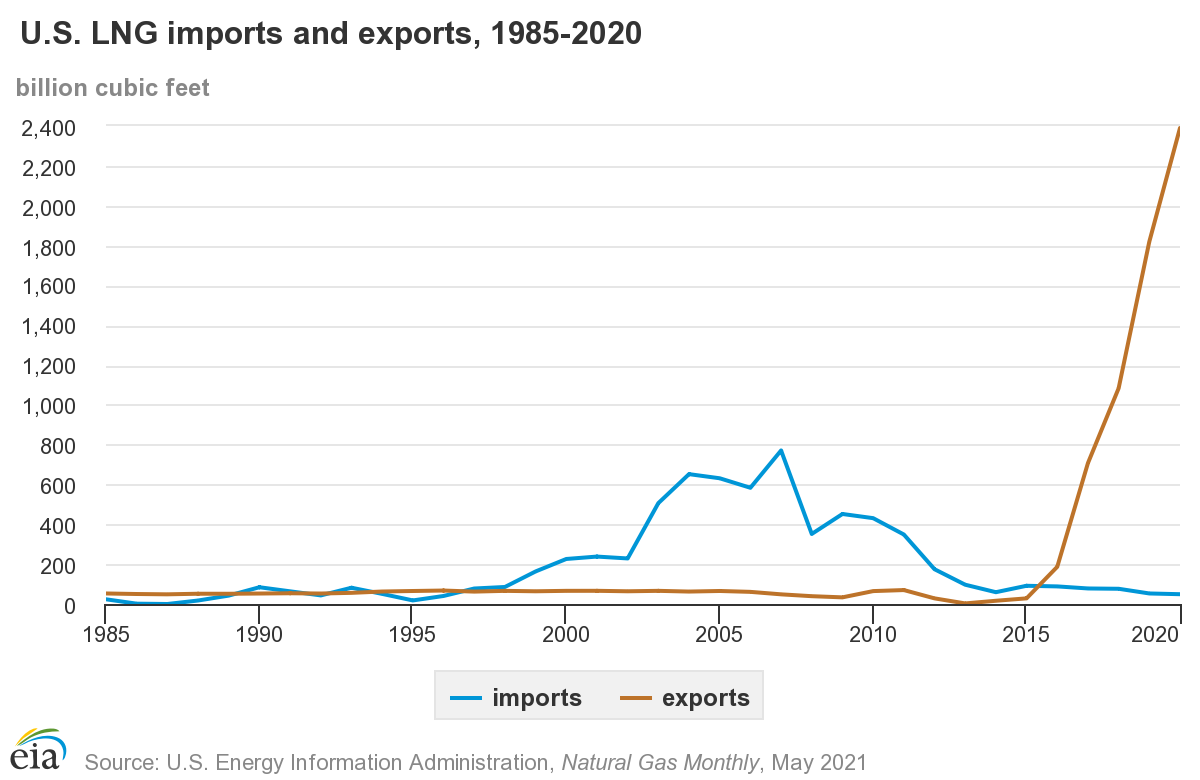

Even less attention is on the U.S.’s tactics. Should the dominoes fall after a Russian invasion, the U.S., now the world’s top exporter of liquified natural gas, will likely avoid criticism for its high-carbon exports.

This is partially because the U.S. has no way to store and transport renewable energy, and partially because of a loophole that doesn’t count fossil fuel exports when tallying a country’s emissions. In this case, liquified natural gas sent from the U.S. to Europe won’t count against U.S. climate pledges.

Instead, the U.S. will likely be viewed favorably: a peacekeeper helping an ally get through a brutally cold winter — and not another large country shirking climate responsibility.

Energy independence is a key goal of any country, and unlike oil and gas, the sun and wind are available everywhere, albeit at varying degrees. The crisis in Ukraine emphasizes this point: We must rapidly transition to cleaner fuels; because if not, we’re leaning on some pretty shaky alliances for energy.

For now, Europe must weather the storm with what is on hand: a mixed bag of dirty energy sources, some imported, some homegrown. The main thing is that the U.S., E.U., and others learn from this crisis.

If Europe doesn’t want to be at Russia’s mercy for the next geopolitical crisis, it’ll get off gas and transition to green as soon as possible.