The train wasn’t an American invention, but at times it sure has felt like it. If laid over Europe, the continental United States would stretch from Spain to Russia, making it seem ripe for train travel.

Historian Stephen Ambrose, writing about the transcontinental railroad, put it this way:

“Only in America was there enough space to utilize the locomotive fully, and only here did the government own enough unused land or possess enough credit to induce capitalists to build a transcontinental railroad. Only in America was there enough labor or enough energy and imagination.”

Yet less than a hundred years after the last spike was driven at Promontory Point, U.S. passenger trains have all but been replaced by cars and planes. Doing some shoddy math, I found that passenger rail makes up a meager 0.16% of all U.S. passenger miles.

For the purposes of this newsletter, this is important, as trains emit only a fraction of climate pollution of cars or planes.

But for years Amtrak, the U.S.’s federally funded passenger rail system, has been an afterthought — one that doesn't work for most people, who value speed, frequency, reliability, and above all, convenience. Kea Wilson recently summed this up for Streetsblog USA:

“What is most toxic about our dominant transportation culture is not cars, or highways, or the emissions that spew out of our tailpipes, but a hyper-individualism that insists that policy should never stand in the way of our individual freedom to move whenever we want, as fast as we wish.”

The assumption then is that American transportation should be a natural extension of our capitalist culture — or at least a culture rooted in productivity and freedom. If that’s the case, though, why are we spending so much money on absolute time sucks like roads and airports? Because I can’t think of a less productive and more restrictive way to spend a morning than stuck in traffic or on a tarmac.

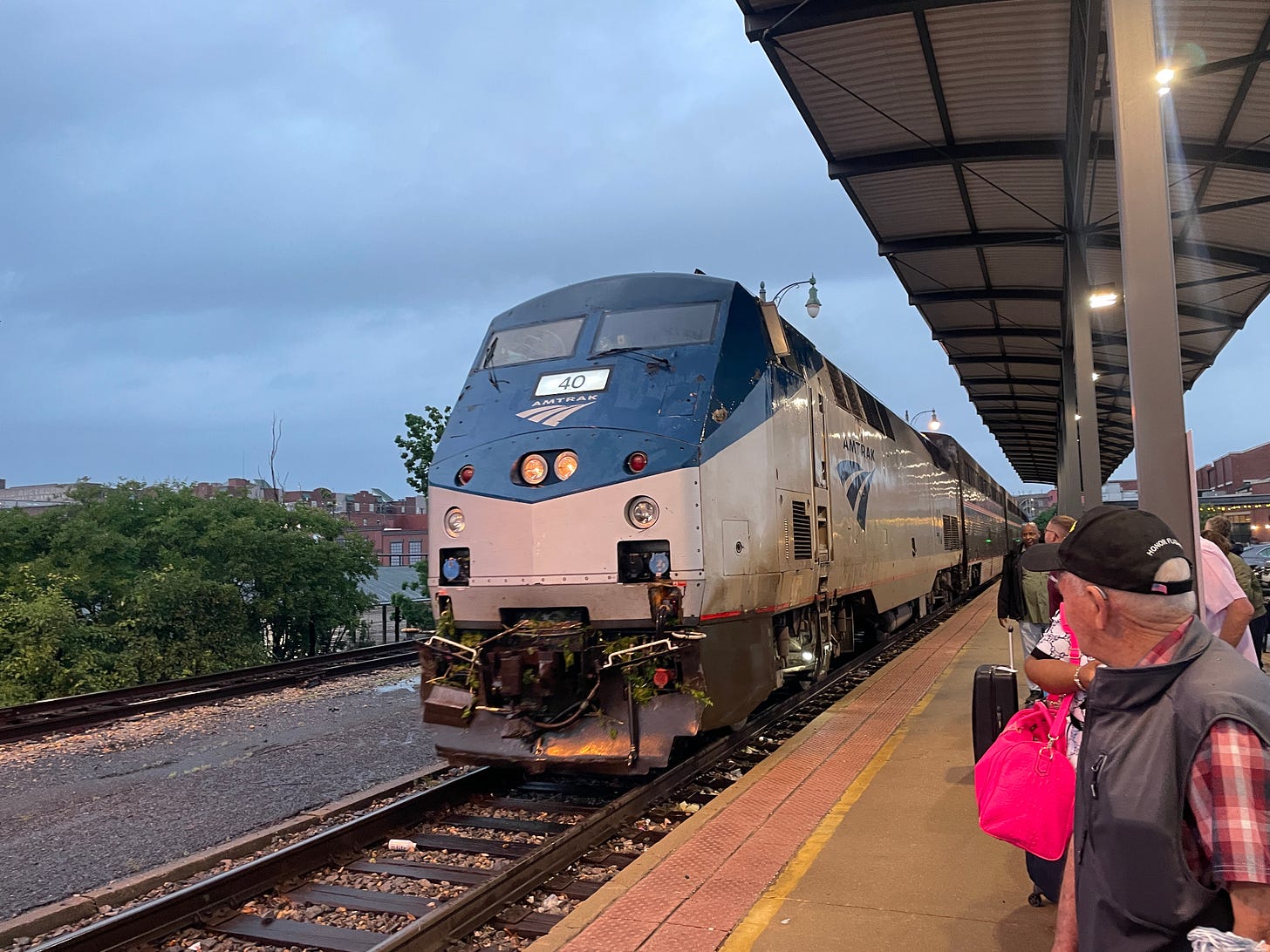

I've been thinking a lot about this because I just completed my fourth cross-country Amtrak trip, this time on a 20-hour train from Chicago to New Orleans. And like in years past, I did so while working.

That’s because trains offer cafe cars, tables, and overall way more space than any other mode of transit. It also requires little of passengers: Once you’re on a train, you can pretty much do whatever — no closing laptops for takeoff and landing, no white-knuckling through stop-and-go traffic.

Between Memphis and Jackson and New Orleans, I worked from the cafe car, with little to no disruption to my workday.

The two days I took off were because of non-train travel: When I flew to Chicago (I couldn’t stomach the 18-hour train from D.C. again) and when I drove to Baton Rouge (no trains operate between Baton Rouge and New Orleans).

Of course, working on trains has limitations. For one, it assumes you work from home. And if you take video calls, you’ll likely experience connection issues (Amtrak’s WiFi is pretty much nonexistent, and a hot spot can only take you so far, especially in rural Mississippi).

But the biggest issue is that American passenger trains are notoriously underfunded.

has an excellent newsletter on the woes of Amtrak, linking its struggles to deferred maintenance, deregulation, diminished planning capacity, poor-performing diesel, and more — all of which creates self-fulfilling prophecy:Without proper and consistent funding for Amtrak, rail services get slashed, which means fewer trains and routes, and maintenance gets deferred, which means trains that do run are slower and less efficient.

In other words, you sacrifice what people want most out of transit: speed, frequency, reliability, and convenience.

The productivity argument — alongside the safety, scenic views, and social aspects of trains — is just one more reason to consider train travel. But unless we more fully embrace and invest in passenger rail like in the European Union, where rail makes up about 7% of passenger miles, people won’t ever get on a train to see that.

Until then, we’ll continue to waste time and money. And for a government that supposedly prioritizes efficiency, that doesn't seem very American at all.

I agree with you completely, but there is another layer. I understand it may not have fit into this post. You also have to consider the state of all other public transportation systems. If you drive your own car, you eliminate the need to procure another means of transportation once you get to your destination. If you go by plane or train, you have to make choices. And this is where socio-economics really pokes it's head in, the choices available are often limited for a variety of reasons. Americans think public transportation is for the poor, thus all the problems you listed due to lack of funding. There is also the difference between metro and rural areas as you encountered. And again, Americans' need for complete autonomy. Especially now, travel is something that the wealthy enjoy and something that the masses have to endure.