Welcome to Planet Days, a roundup of the latest climate news and what it means for our Planet. If this was forwarded to you, smash that subscribe button:

It’s Friday, which means we’re giving you a three-minute take on a big climate story from the week. This morning, that story takes us to the crisis in Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine has disrupted global energy supplies, forcing countries to quickly transition from Russian oil. Here’s a quick recap to date:

The U.S., E.U., and the U.K. have all cut Russian imports of oil and natural gas. To stabilize soaring gas prices, countries have released oil from their strategic reserves.

Countries like the U.S. are now increasing liquified natural gas exports and finding other ways to close the gap left by cut-off Russian imports.

At home, Republican lawmakers and oil companies are calling for more domestic oil and gas drilling. Democrats, meanwhile, are pushing for carbon-free sources.

That’s a lot of fossil fuel talk. But amid all the calls for energy independence, one carbon-free source flies under the radar: nuclear power.

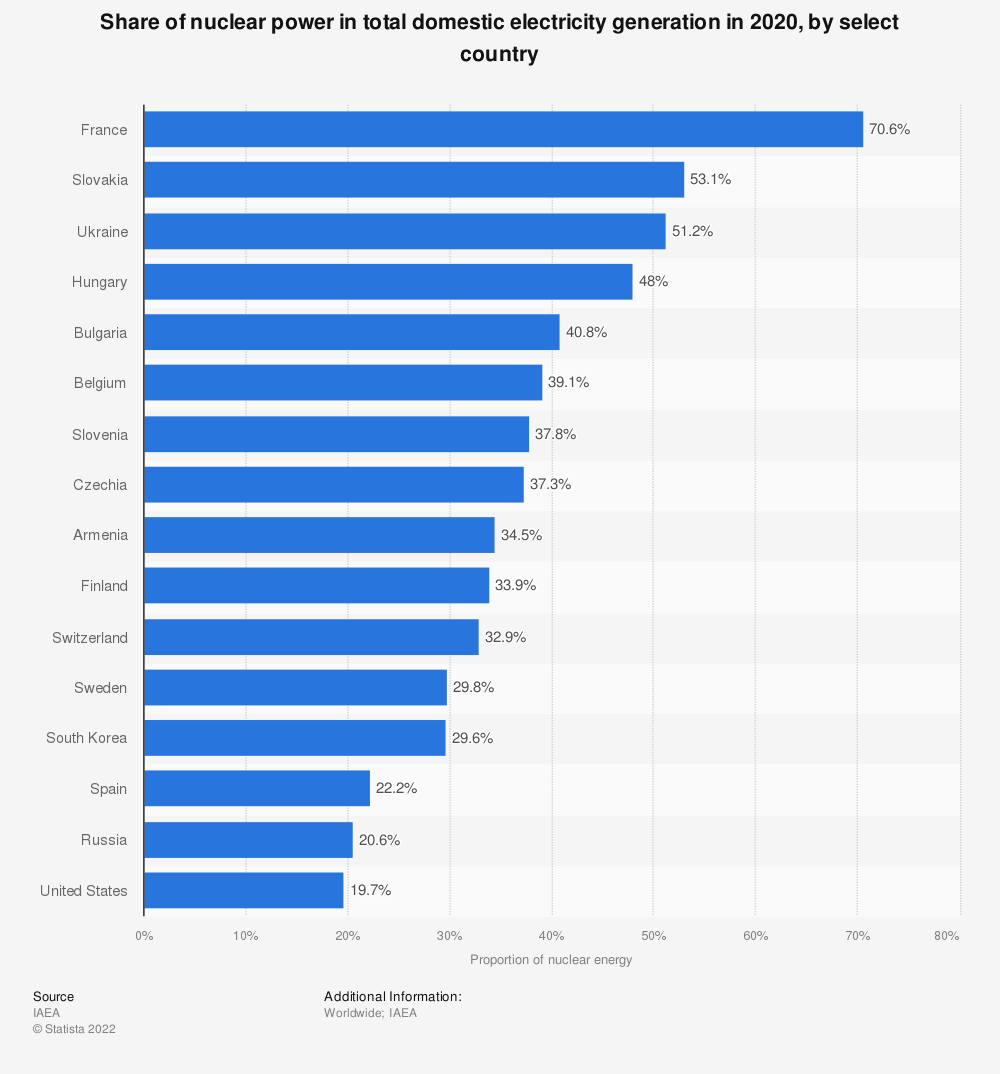

Nuclear power produces 24.6% of all electricity in Europe and 18.9% in the United States. Though that’s a big chunk of electricity, many leaders are still skittish to go all-in to nuclear energy — and understandably so.

The war in Ukraine highlights a very real argument people have against nuclear energy. Ukraine’s nuclear reactors, of which they have 15, have been in the line of Russian fire, prompting fears of a meltdown that would threaten all of Europe. Military activity near Chernobyl could also set off a disaster.

Of course, that’s what makes nuclear power such a Faustian bargain: On the one hand it’s a carbon-free source that delivers us from fossil fuel evil; on the other, a nuclear meltdown has devastating consequences for the environment and humanity.

Put another way, nuclear is what the nonprofit organization Project Drawdown deems a “regrets solution,” or one that can hurt society, the environment, and economy:

“Regrets include tritium releases, abandoned uranium mines, mine-tailings pollution, spent nuclear waste disposal, illicit plutonium trafficking, thefts of fissile material, destruction of aquatic organisms sucked into cooling systems, and the need to heavily guard nuclear waste for hundreds of thousands of years.”

Not a list to take lightly. And yet.

Project Drawdown still lists nuclear energy in its top 50 solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, nuclear energy generation must increase, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Overall, nuclear power done right can decarbonize the grid, complemented by next-generation nuclear reactors that are safer and produce less waste.

I’ll end with this case study of France and Germany, neighboring countries with very different approaches to nuclear energy:

Germany gets 12% of its electricity from nuclear power and is phasing out coal and nuclear for renewable energy, with the aim of closing remaining nuclear power plants this year.

But Germany is also hyper-reliant on Russian energy, more so than many European countries. It’s why the Nord Stream 2 pipeline — which would have carried Russian gas to Germany and is now defunct — existed in the first place.

Absent the nuclear power that once existed within its borders, and cut off from cheap Russian gas, Germany is turning to fossil fuels, building two liquefied natural gas terminals and boosting its natural gas reserves.

France, meanwhile, gets over 70% from nuclear power, more than any other nation. Recently, France doubled down on nuclear, with a plan to build six new nuclear reactors and extend the life of existing plants.

That nuclear energy is in part why France imports much less Russian gas than Germany: The country only obtains a quarter of its gas from Russia, while Germany imports around half of its supply from Russia.

France isn’t on an island here. The United Kingdom and Finland, which shares a border with Russia, are also turning to nuclear energy to wean off Russian imports.

As with anything, there’s no silver bullet solution to the climate crisis. And while we turn to solar and wind, we may also need to make room for nuclear power — a tough, but necessary, pill to swallow.